Lake Tashmoo Storm Water Remediation Project: First Flush Leaching Basins More Effective Than Expected

| Contact:

Jane Peirce

Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection

627 Main Street

Worcester, MA 01608

508-767-2792 | Jane.Peirce@state.ma.us

|

Primary Sources of Pollution:

| |

| storm water runoff

|

Primary NPS Pollutants:

| |

| suspended solids

|

| fecal coliform bacteria

|

Project Activities:

| |

| 12 first flush leaching basins

|

Results:

| |

| 91 percent decrease in fecal coliforms

|

| 98 percent decrease in total coliforms

|

| elimination of oil, grease, barium, chromium, and lead

|

| shellfish beds reopened

|

<tbody>

</tbody>

Contamination from storm water runoff, particularly suspended solids and fecal coliform contamination, has forced many shellfish beds and public bathing beaches along the Massachusetts coast to close. The closures can range from a few days to the summer to the entire year, depending on the type and level of contamination. The town of Tisbury on the Island of Martha's Vineyard has numerous "hotspots" where access to shellfish beds and public beaches has been restricted because of storm water contamination. The residents of Tisbury rely on fishing and tourism for their livelihood, so it is imperative for the town to find ways to effectively treat storm water contamination.

At 1 mile in length, Lake Tashmoo is one of the larger of the saltwater lakes on the island that feed into the sea. It is an ideal habitat and breeding ground for oysters, scallops, clams, mussels, crabs, lobsters, and a variety of fish species that serve as the food source for larger fish, all of which are commercially harvested as the backbone of the island's fishing industry. In addition, the lake has a major beach area, a town dock, and boat moorings and is used for swimming, sailing, wind surfing, boating, and sportsfishing.

Before 1994 hard shell clam, mussel, and scallop beds near the storm water outlet were showing contamination from fecal coliform bacteria, heavy metals, and oil and grease. The Division of Marine Fisheries routinely closed the beds after large rainfall events because of fecal coliform levels in the water. The contaminant levels were consistently high enough that the shellfish beds were on the verge of seasonal closure, which would have effectively put the resource off-limits to the local townspeople and to the large seasonal population that flocks to Martha's Vineyard during the summer months. Recreational use of the lake is a major tourist attraction, and the town considered maintaining the lake in a viable and usable state imperative.

Adding leaching basins

In 1994 Tisbury Waterways, Inc., and the Town of Tisbury received 319 funding to install a series of 12 "first flush" leaching basins along road drains to capture and treat the road runoff that was contributing to the contamination of highly productive shellfish beds at one end of Lake Tashmoo. The first flush basins, installed along a 1.6-mile stretch of road, were designed to treat the first ¼ inch of rainfall, which contains most of the contaminants.

Each basin consists of a 6-foot by 6-foot perforated cement vessel filled with limestone, surrounded by a gravel bed. The limestone in the basins is covered with hydrophobic, oil-absorbing pads, which help to separate the hydrocarbons from the runoff. The limestone in the pits raises the pH of the runoff, causing heavy metals to precipitate and accumulate in the pit. Finally, the first flush basins provide additional residence time for fecal coliform bacteria to oxidize and decay. The treated runoff then passes through the gravel surrounding the pits into the subsurface soil.

Exceeding expectations

Comparison of contaminant concentrations in Lake Tashmoo before and after installation of the basins showed significant improvement in water quality. Samples from Lake Tashmoo during rainfall events showed fecal coliform and total coliform levels going down by 91 percent and 98 percent. Oil and grease could not be detected in the treated effluent; barium, chromium, and lead, which had all been present before installing the basins, could no longer be detected in the effluent. The project was deemed a success and recommended as a model for other storm water hotspots around Tisbury.

The system is exceeding the town's initial expectations. Although it was designed to capture and treat the first ¼ inch of storm water runoff, the system appears to be capturing and treating the first ½ inch of runoff. The sandy soils that underlie the leaching catch basins allow the treated storm water to percolate into the ground more quickly than the designers anticipated, thus allowing the system to capture additional storm water.

As a result, since the basins were installed there has been no discharge at all to Lake Tashmoo during moderate rains. Even during heavy rainfall, less storm water is discharged into the lake and the water continues to be of significantly better quality than before the basins were added. The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries has continued to monitor water quality at the shellfish beds. The beds have not been closed during the past several years, and there is no longer any thought of seasonal bed closure.

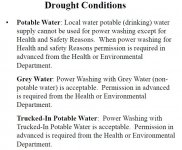

Robert Hinderliter Notes: I do not believe it is proper to add Power Washing Waste Water to these beds.

I believe is similar to Street Sweeping: If you sweep a street, then discharge our dirt into the MS4; is that good BMPs? Or does the dirt need to disposed of somewhere else?

So why would you discharge your Power Washing Water into these StormWater Remediation Devices when they are not designed to accept this concentrated waste?